Originally written for OpenVC, How to Model a Venture Capital Fund

As a prospective or emerging fund manager, you will spend most of your time crafting your investment thesis, and detailing how and why founders and investors should work with you, towards creating a point of view on how you will create a successful venture fund.

Creating a financial model for your fund allows you to detail your thesis and strategy in quantitative terms, to create some expectations for how you will spend your investors’ capital and generate returns on your investments.

While creating a financial model for a venture capital fund is difficult, given the speculative nature of forecasting investment results, the act of creating a forecast is still valuable, as it allows you to:

- Outline to potential limited partners the fund’s expenses, your fees for operating the fund, and their expected capital calls

- Reflect your investment strategy, primarily in terms of check sizes, follow on reserves, and investment deployment timelines, and make sure that your strategy reflects reasonable benchmarks and expectations

- Create a forecast of capital reserves and operating budgets so you can plan capital deployment, hiring, and operational strategies

- Demonstrate to potential limited partners that you have a solid plan on how to deploy capital towards your investment thesis

- Create a point of view on how your thesis aligns with typical investments in your industry, and create a grounded range of expectations of how those investments will generate returns

As the founder of Foresight, and an ex-venture capitalist, I’ve worked with over nine hundred emerging and prospective venture fund managers creating financial models for portfolio construction and operating cash flows for their first funds. I’ve worked with managers that have raised hundreds of millions of dollars from limited partners around the world, mentored at accelerators for prospective fund managers, and worked directly with angel investors and venture capitalists analyzing their investment portfolios and potential returns.

My goal from this post is for you to come away with a solid idea of what it means to create a financial model for a venture capital fund, the various ways you can create a portfolio construction and operating cash flow model, and provide you with templates and examples that you can use for modeling your fund.

Before you get started

Modeling a venture fund typically consists of two models:

- A model for the fund, the entity making the investments

- A model for the management company, the entity managing the fund (or multiple funds)

Modeling the management company is similar to modeling any operating company, and typically consists of modeling revenues - primarily management fees from the fund(s) - and expenses - salaries, overhead, legal, accounting, travel, etc. - to create a forecast of cash flows and financials.

This post will focus on creating a model for a fund, not for the management company. Budgeting the Management Company of a Venture Capital Fund covers modeling a management company in detail.

Modeling a venture fund can vary from modeling other types of private equity investments. Private equity funds and real estate investment funds often have fund structures and expectations in how and when proceeds are received that differ substantially from venture capital funds. Similarly, hedge funds have different structures and expectations around investment and limited partner liquidity, making them substantially different from venture funds. Open-ended venture funds, evergreen funds, venture debt, revenue-sharing venture funds, and fund of funds share many similarities regarding capital budgeting and deployment, but often differ in the timing and nature of proceeds and recycling. For this post, we will focus on closed-ended venture funds making investments into equity or equity-like structures (convertible notes, SAFEs, SAFTs, and other token structures).

Contact me if you have questions on modeling alternative venture structures.

The best models for venture funds are built with the intent of reflecting their investment strategies. Extreme outcomes from a small number of investments usually drive overall portfolio returns, and the resulting power laws make it difficult to create deterministic forecasts of when and how these extreme outcomes will happen. I focus on creating models that help managers understand their strategies, using their expectations of their investment thesis to understand if their strategies “work” based on their assumptions.

Tools to build a model

Spreadsheets - primarily Microsoft Excel and Google Sheets - are the most common tools used to build financial models for venture capital funds, because of the accessibility and familiarity that most emerging managers have with the tools. Many modelers will use add-ins to assist with scenario modeling to help understand the impact of variability in their assumptions, and a number of tools for Monte Carlo and scenario analysis are readily available to help understand portfolio construction assumptions and ranges of expected returns.

A few prebuilt templates in Excel or Google Sheets include:

- Airstream Alpha's Fund Financial Budget Template

- Hadley Harris' Portfolio Construction for Dummies

- Sam Gerstenzang's Open Source Venture Model (V1)

As well as models created by me:

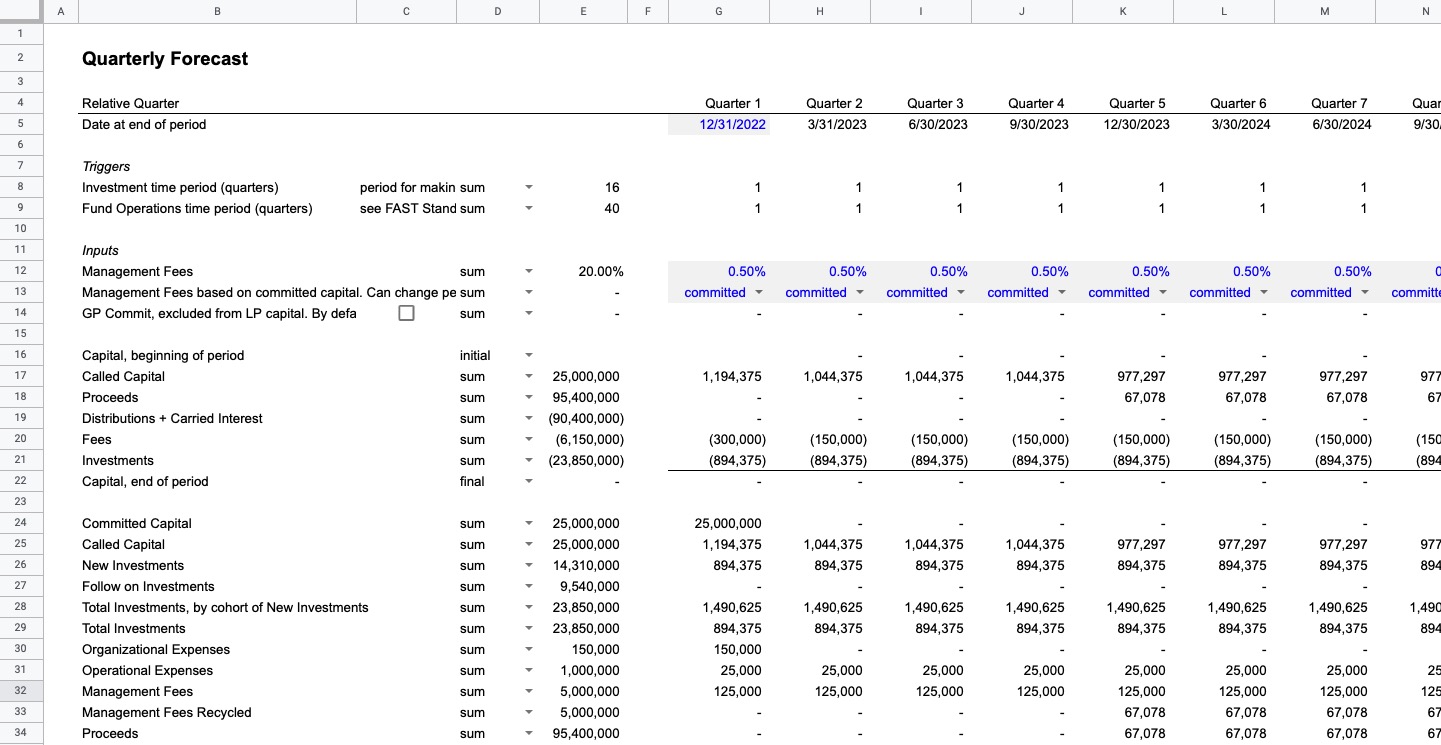

- Foresight's Venture Capital Model (Annual Forecast)

- Foresight's Venture Capital Model (Quarterly Forecast)

Articial Intelligence-enabled modeling tools like Shortcut and generalized LLM providers like ChatGPT, Claude, and Microsoft Copilot can be used to create spreadsheet financial models, but at this point with my tests their understanding of how venture funds works is not sufficient enough to create accurate, workable models, and thus at this point I cannot recommend using them to create models for venture capital funds. Even their understanding of basic cap table calculations is not to be trusted.

Web-based financial modeling tools that can be used to build financial models for venture funds are few and far between. Carta Fund Forecasting (formerly Tactyc), is a platform for fund managers to create and manage venture portfolios, which includes a range of features to help fund managers understand portfolio construction and fund management. Using this platform requires a demo by Carta and a Carta subscription.

The 10 components to building a venture fund model

The first consideration in building a model for a fund is whether you want to model the overall fund, or whether you want to add on modeling the cash flows over time. Modeling the total fund investments and returns, without considerations for when those investments and returns happen, is a simple exercise and can be useful for basic understanding of fund strategy. Adding the notion of timing of when significant events in your portfolio happen - write-offs, unrealized gains from markups in investments, proceeds from exits - adds in richer detail to understand the cash flows over time and develop an appreciation for the key metrics that managers are judged on.

For your first attempt at building a model, start simple by modeling the total fund investments and returns, which would likely be a one or two sheet model. As you develop your competence in modeling and understanding of venture economics, add in more complexity and detail to your model. When it comes time to start making investments, you will want to have a model that captures cash flows over time so that you can properly budget and plan for your investments, reserve capital for follow-ons if that is part of your strategy, and start to plan for the future of your fund. While a fund model may not be the central focus of your fundraising process, it will typically be required in due diligence, and it can be a valuable way for you to demonstrate to potential limited partners that you have fully thought through what it takes to run a fund.

Capital Budgeting

Capital budgeting is the process of determining how much money you can invest. At the simplest level, overall invested capital is typically:

Committed capital

- organizational fees (expenses incurred to set up the fund)

- fund operational fees (operational expenses paid by the fund)

- management fees (fees paid to the management company to operate the fund)

+ recycled proceeds (recycled proceeds back into the fund, often expressed as a percentage of management fees or a percentage of fund committed capital)

= Invested capital

The budget can be created for just the overall amount invested, or can be created to show the budget for multiple periods over time (per year, per quarter, per month) if you are modeling cash flows over time. The primary driver of your budget for capital to invest is your fund size, or total committed capital. Out of this, the fund entity will pay a number of expenses, and the remainder is available for the fund to invest.

Organizational Expenses

Organizational expenses include out-of-pocket expenses paid to set up and organize the fund, which can include the legal costs to draft and execute the limited partnership agreement (LPA) as well as costs incurred by the general partners to source and close limited partners' commitments to the fund, up to a cap or maximum amount defined in the LPA. Organizational expenses will typically only incur at the very beginning of the fund, or only in combination with each close of new committed capital into the fund.

Operational Expenses

Operational expenses, or partnership expenses or fund expenses as defined in many LPAs, are the expenses bourne by the fund to administer and maintain the fund entity, which will typically consist of fund administration expenses, taxes, audit, fund legal costs, and additional expenses outlined in the LPA related to the management company's administration. Managers of the fund have some discretion for what expenses to charge to the fund, typically up to an annual and/or total cap defined in the LPA, and managers typically aim to limit expenses paid by the fund. These expenses often scale by the size of the fund, due to the increased costs in managing larger funds with more limited partners (LPs) and often more regulatory burdens. Fund administration expenses are typically paid quarterly, while tax and audit are bunched around Q4 and Q1 to reflect the timing of fiscal year and tax filing responsibilities. Additional partnership expenses, including expenses related to portfolio company administration, oversight and administration to the fund and their limited partners, and perhaps investment marketing and due diligence, may be charged to or partially allocated to the fund and the management company and trued up quarterly based on the terms of the LPA. Operational expenses may also have a cap or maximum amount that can be charged annually or over the lifetime of the fund.

Management Fees

Management Fees are typically defined as a fund expense, and are paid by the fund to the management company to pay the managers for executing on the fund's investment strategy. The managers of the fund use these management fees to pay for the expenses incurred by the manaagement company, including salaries, marketing, rent, travel, legal, and typical operational expenses.

Venture capitalists often describe the fees paid by limited partners as a "2 and 20" model, reflecting the general standard of 2% management fees and 20% carried interest. Note that while management fees may be commonly thought of as 2%, that is an annual cost, and for a ten year fund the total management fees would be a total of 2% * 10 or 20%. Management fees are generally charged for the lifetime of the fund defined in the LPA, and generally not charged during any fund extension periods defined in the LPA or agreed to by limited partners. Management fees are typically paid quarterly by the fund to the management company.

That said, there are variations from the typical structure.

- Fees may change over the fund lifetime. It is not unusual to charge higher percentages during the investment period, and then decrease during the later periods (often thought of as the harvesting period), and it may change often depending on how the managers and limited partners choose to structure it. The idea is for the higher fees in the early period to help the general partner pay for the higher operational costs associated with sourcing and supporting investments in the earlier years of the fund. A fund could be structured for a single stepdown or multiple stepdowns, depending on what the general and limited partners agree to. For example, a fund could pay 2.5% for the first five years and 1.5% for the next five years, resulting in the same total of 20%. Or a fund may change the fee every year, there are many potential ways to structure it.

- Different limited partners may pay different fees. For example, early committed or large limited partners, including "anchor" investors, may pay reduced management fees (and carried interest) as compensation for their role in helping provide positive signals to other investors. Philathropic capital may pay zero fees, or may not require any returns above return of capital, or cover early losses, as their role as a catalyst in helping support a fund's investment mandate. In addition, the capital invested by the general partners into the fund, the GP commit, typically will not pay management fees or carried interest.

- Fees may be calculated in different ways. The standard is to charge fees as a percentage of total committed capital, or fund size (e.g. 2% * total committed capital, charged every year). It could also be structured as a percentage of total called capital to date, or a percentage of assets under management. Assets under management could be defined as invested capital (average during a period or total at end of period, reflecting currently invested capital or cost basis of current portfolio companies, meaning that invested capital goes up as the fund makes investments and goes down with writeoffs or exits) or as the net asset value (NAV) of investments, meaning the value of the unrealized gains in the current portfolio may also be included.

- The basis for calculation may change over time. As one example, funds may structure fees to be calculated as a percentage of committed capital for the first five years, and a percentage of assets under management for the next five years.

For funds that are holding multiple closes on their committed capital, it is important to note that holding multiple closes will not change the total fees paid by the fund over it's lifetime, as later investors will “catchup” on fees that they would have paid in earlier period, so that all limited partners have the same prorata cost basis and allocation of expenses for the fund.

To understand the size of organizational and operational fees, the best method is to talk to other fund managers or talk to the service providers directly for their quotes on expenses for your fund. Many providers - Carta, AngelList, Allocations, Anduin, Assure, and others - provide online pricing estimates.

VC Lab has a good overview on managing fund expenses to understand what should be charged to the fund and the management company, what type of expenses to expect, and some help on how much to budget for fund operational expenses. They also provide a sample limited partnership agreement free to download, called the Cornerstone LPA.

Portfolio Construction

Once you’ve created your capital budget and decided on the core timescale necessary for your current needs, the next consideration is how you want to approach portfolio construction. Portfolio construction is the process of creating your portfolio strategy, check sizes, follow on reserves, and expectations around valuations, ownership, and dilution over time.

Portfolio construction at its core is making choices between trade offs, including choices such as:

- Should the fund be concentrated or diversified? Meaning, should the fund invest in a small or large number of companies, relatively?

- What check size should the fund target? What check size makes sense given the fund's perspective on targeted ownership percentage, stage of investment, and strategy to lead or follow?

- How many companies should the fund invest in? At a given fund size, larger check sizes means a smaller number of investments.

- Should the fund reserve for follow-on investments? Investing in follow-ons can be an important part of a fund's investment strategy, but also reduces the number of new investments that can be made.

These choices matter, as funds have to consider their target portfolio size and whether the number of companies they are investing in gives them the opportunity to invest in a large exit or "winner". Small, concentrated portfolios gives funds less chances to be invested in a large exit, which are statistically a small percentage of the total companies founded every year, but large portfolios can create logistical and operational challenges in terms of sourcing and supporting a large number of companies that have to be balanced against the gains from diversification (the gains from diversification reduce after a certain protfolio size).

At a given fund size, larger portfolios also mean smaller check sizes, which gives companies a smaller ownership in companies and potentially impacting the "return the fund" math underlying venture capital returns. High performing funds are typically driven by (a) a larger number of large exits and (b) the larger size of those exits. Smaller check sizes means lower initial ownership and a lower total return from large exits, meaning a fund has to be right on a larger number of exits in order for the fund to perform. Many investors will operate under the idea that every investment they make has to have the potential to return the fund - return capital to investors plus potentially generate additional returns for general partners - which has implications for target ownership size, initial check size, and follow-on strategy and approach to dilution.

Should you build a concentrated fund? at Signature Block is a good discussion of the tradeoffs and perspectives on portfolio construction.

There are multiple ways to build portfolio construction in a fund model:

- Specific investment. In this approach, instead of assuming an average investment, we create specific assumptions around each new and follow-on investment made (modeling the timing and check sizes) as well as the exits (modeling the size and timing of proceeds from those investments). This approach is also often used for portfolio tracking, to track portfolio performance or budget reserves for follow-ons and return expectations from the portfolio. See my free Excel model for this approach.

- Average investment. In this approach, you would assume the average new investment (check size) and the allocation of capital to new investments and follow-on investments, and assume an overall return multiple on invested capital. This is the simplest approach, and works well for initial analysis, if you are not pursuing a follow-on strategy, and if you do not need a lot of detail around your portfolio construction. See my free Excel model for this approach.

- Detailed cap table. In this approach, we use the same assumptions as above, but detail out the capital allocated, check size, and expected participation into each follow-on round of financing. As part of this, we will often detail out the expected future rounds to show how ownership changes over subsequent rounds, show our dilution, and estimate returns and changes in investment value over time. See my Excel model for this approach.

There is no single right way to approach portfolio construction, and the “best” way to forecast a portfolio depends on your specific needs. More detail may sound appealing, but requires more assumptions and may not be necessary for your needs. If this is your first fund and you’re in the early planning stages, start with the first approach. If you have a set of investments you know you are making (or have already made), start with an approach that uses specific investments. If you are thinking about portfolio construction and allocation to follow-ons and what to think through the mechanics of dilution and returns, start with the average investment or detailed cap table approach. Ultimately the question to ask is how you plan on using your model, what decisions you will make with it, and your ability to create, use, and manipulate the important decisions in your model.

Returns Expectations

The methodology to forecast return expectations is often determined by your approach to portfolio construction, but the simplest method is to assume a gross exit multiple for your invested capital.

Gross exit multiple * invested capital = proceeds from investments

Proceeds from investments are then distributed to the investors in the fund, typically defined as the fund’s limited partners. Distributions are capital paid back to the investors, and can vary from proceeds received depending on recycling provisions or other agreements with limited partners. A schedule of distributions is often called a waterfall, which depicts the flow of capital to investors based on the fund’s agreements with it’s investors. Typically limited partners are first paid back the capital they invested, perhaps with a preferred return or after accounting for a hurdle rate of performance, and then general partners start to receive carried interest, or a percentage of the distributions paid based on the performance of the investments.

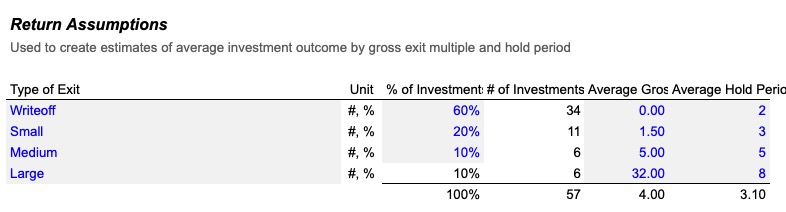

Fred Wilson has a foundational post on modeling fund economics at Venture Fund Economics, Gross and Net Returns

In many models, a straightforward way to model return economics is to create an input to assume a gross exit multiple, then calculate gross proceeds using that multiple. You can get more detailed by assuming different gross proceeds multiples for different types of investments, different stages (new and follow-on, by stage), or just an overall blended multiple. A typical method to add more detail is to create a table of types of exits - zero, small, medium, large, etc. - and the gross exit multiple per type of exit, and the % of companies that achieve each exit, to calculate an overall blended proceeds multiple that provides more color to the investment strategy.

This method abstracts away how the multiple occurs, and does not require one to model the underlying changes in the invested capital post-invested. Meaning, it does not model out ownership, dilution, the impact of additional rounds, time to exit, or the different stages and multiples that exits can occur. If desired, using the more detailed portfolio construction methods to show the rounds of financing that occur post-investment - on an average or specific-company basis - can help detail your expectations of how many companies raise additional capital, how large the rounds are, how much your ownership is diluted, when potential exits can happen, and the different exit points you expect to see in your investments.

Creating an expectation of entry valuation, overall dilution, and average exit can be helpful to ground your gross exit multiple assumption. If worthwhile, creating a more detailed portfolio construction can help show how you expect to earn the gross exit multiple.

Capital Deployment

Capital deployment modeling involves creating a schedule of investments, fees, and capital calls over time. The easiest way to model a fund is to not do this, meaning just model the overall investments and exits without accounting for when they happen, but if you decide that it’s important to create a time-based forecast, then you will have to create a capital deployment schedule.

Most managers will want to start this by assuming an investment timeframe, in terms of quarter or years, post-close of the fund where new investments will be made. Then you can average out the deployment of capital allocated to new investments over this timeframe.

If you are investing in follow-ons, typically you will assume deployment of capital into follow-ons using an assumption of time from initial investment to each follow-on round that is part of your strategy. This will extend outside of your investment timeframe.

With this forecast of invested capital per period (quarters, years), then you can create a forecast of management fees and operational fees per period, to create a schedule of called capital. Many funds will call capital according to investments plus fees per quarter, but some funds will call capital annually, or based on need for new investments and operating expenses, or if the fund is smaller, call a significant portion or all capital up front, upon fund close. Regardless, once you’ve forecasted investments and fees, then you can apply the logic for calling capital, and create a forecast of available fund capital:

Capital Available, beginning of period + called capital - management fees - operational and organizational fees - invested capital = capital available, end of period

Many funds will additionally want to create a forecast of reserves for follow-on capital, based on their schedule of new investments, to show how they are budgeting capital for potential follow-ons. For forecasting a new fund, this isn’t typically too important because your forecast of new and follow-on investments and called capital implicitly assumes this, but once you start tracking actual investments and can apply some logic to different expectations of follow-ons for specific companies, creating a capital reserves forecast can be very important to help for capital deployment budgeting.

Realized Cash Flows

If you are creating a time-based fund model, you will likely want to create a forecast of proceeds and write-offs (when the value of your investments in companies are marked down to zero, likely because the company went out of business). The typical method is to use your earlier assumption of gross exit multiple and an assumption of average hold period, and then calculate when proceeds happen and how large based on your capital deployment schedule.

Proceeds from investments are then either recycled back into new investments or distributed to investors in the fund.

Waterfall Distribution of Proceeds

A waterfall depicts how the proceeds are distributed to the investors and managers of the fund, according to the funds’ provisions.

- In a typical USA-based venture fund, a waterfall just involves modeling the return of capital to the limited partners, then any distributions above that multiplied by the fund’s carry to calculate carried interest. An additional level of detail that can come into play is if the fund is using a tiered carry approach, where the carried interest percentage increases as the fund hits certain return benchmarks as specified in the fund agreements.

- In many non-USA venture funds (and US private equity funds), there are additional structures that can complicate waterfall modeling. Preferred returns - commonly cited as a percentage return on invested capital - or a hurdle rate - a required rate of return on invested capital - serve to provide first returns to limited partners before general partners can share in the distributions, although terms such as a general partner catchup can allow general partners to earn back the carried interested they would have earned on the preferred return, if there are sufficient proceeds.

For an overall portfolio model, this can be fairly simple to model, as you do not need to account for who receives distributions when, but for a time-based model, it gets more complicated as you will need to track the distributions of proceeds against called capital to show the return of capital to limited partners, potentially the distributions to pay for the preferred return and optionally GP catchup, and then the split of distributions between limited partners and the general partners based off the carried interest earned by the general partners on the proceeds.

Unrealized changes in the portfolio

An additional option in building your fund model is whether you want to show the changes in valuation in the underlying portfolio. Residual value is the current market value of the investments, which represents the sum of current invested capital (investments made, less any write-offs) plus unrealized gains from increases in value of the investments. Most funds will mark up their investments based on updated valuations of their companies, particularly when they raise new rounds at different valuations.

Modeling these underlying changes in the portfolio is only necessary if doing a time-based model, since once all investments are exited, residual value is equal to zero. It can be complicated to add this to a model, but is necessary for understanding the value of a portfolio when the fund is still deploying capital or not fully exited. Personally, I think this is valuable to add for any investor managing other people’s money, so that they can provide the level of detail and communication around performance reporting that limited partners should demand.

Mechanically, typically you will have to use a detailed portfolio construction approach to show the expected timing to write-offs, additional funding rounds, and exits to create a schedule of current invested capital and unrealized gains, increasing them when new investments are made or when investments are marked up, and decreasing them when investments are written off or exits occur.

Performance Metrics

Two primary metrics are used to evaluate all types of investments, IRR and return multiples. You will want to create a model to report two variations of these, by gross and net:

Gross multiple = proceeds / invested capital

Net multiple = distributions / paid in capital

The key difference between these is that gross highlights the performance of the investments, net highlights the performance of the fund by including expenses (carried interest, management fees, and other operational and organizational expenses).

You will also want to detail gross and net IRR, and typically the best way to do this is to create one line to show gross cash flows per period, and one for net cash flows per period - using the same definitions for gross and net above - and then use IRR or XIRR functions in spreadsheets to calculate IRR.

If you are creating an overall portfolio model only, calculating multiples will be straightforward, you can estimate IRRs by using the total returns and an expectation of the fund’s lifetime. Using a time-based model will allow you to report IRRs more robustly.

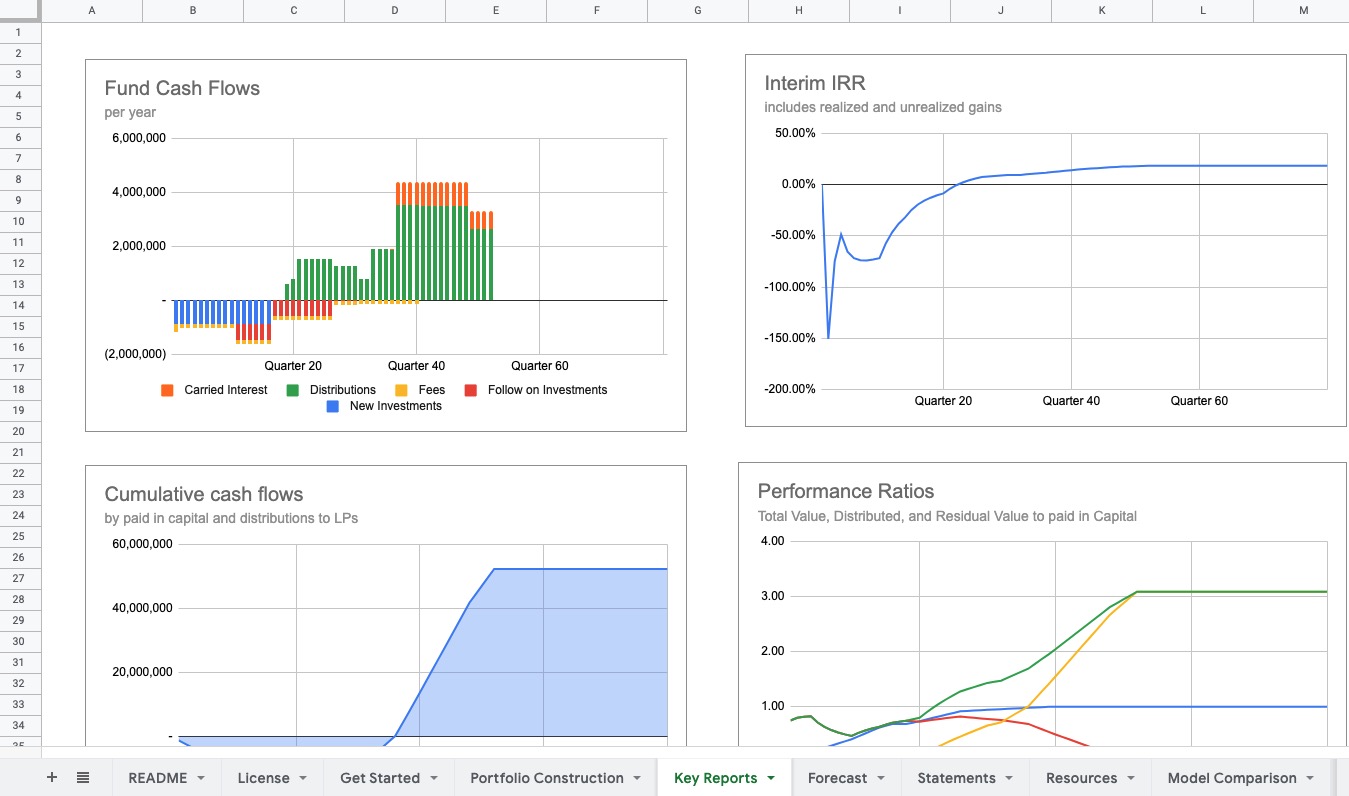

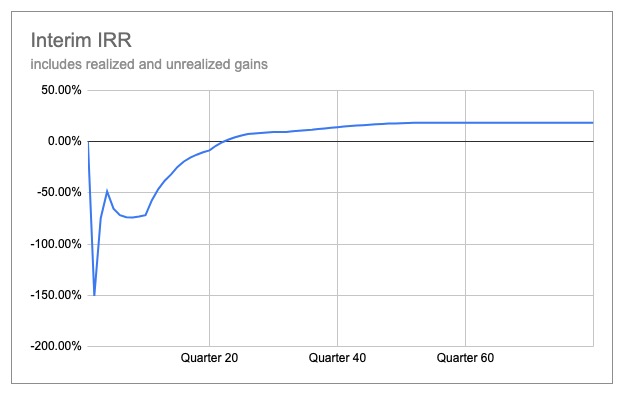

By definition, these metrics only measure realized returns, so they only tell part of the story for a fund that is currently investing and not fully exited from their investments. Interim IRR is an additional metric that allows you to include the unrealized value of your investments in your “proceeds”. Mechanically, this requires building a per-period cohort approach to model out the cash flows and total residual value at the end of each period, and calculate Interim IRR per each forecasted period. Since Interim IRR will equal overall IRR at fund exit, this is only valuable to show the changes in value over time. Typically funds will forecast this to show their expected J curve, to show the negative IRRs early (since you will call capital, and your investments will be less than called capital because there are fees to operate the fund) and then rise over time as investments are marked up and exits occur.

All Foresight models that model cash flows over time include a prebuilt section to model Interim IRR.

Structurally, I typically model interim IRRs based on paid in capital, but do not include expected carried interest, so Interim IRRs usually rise and then decline over time to overall net IRR as residual values are taken off and distributions net of carried interest occur. More complicated approaches could factor expected carried interest into their calculations.

For a deeper discussion of interim IRRs, I highly encourage you to read Allen Latta’s post on IRRs. He has a number of posts that dive deep into the mechanics of funds that are great resources for fund managers.

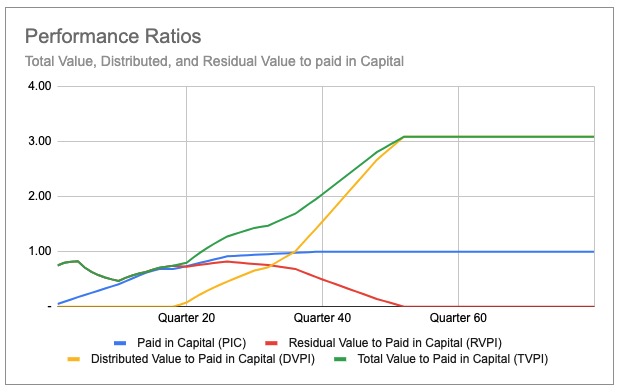

When modeling funds over time, you will also want to include four key performance metrics to aid in benchmarking and quick communication of returns:

- Paid-in Capital, or portion of current cumulative paid-in capital to total committed capital

- Residual Value to Paid in Capital (RVPI), showing current residual value (less estimated carried interest) divided by current paid in capital

- Distributed Value to Paid in Capital (DPI), showing current cumulative distributions divided by paid in capital

- Total Value to Paid in Capital (TVPI), showing total value from distributions plus residual value, divided by paid in capital. TVPI = DPI + RVPI

The key to these metrics is that they explain different things about the fund’s performance; RVPI highlights how much value in the fund is in the current investments, and DPI reports how much has been distributed to investors. At fund exit, RVPI = 0 and DPI = TVPI, so if you are creating an overall fund model, these metrics will not be as relevant as the multiple and IRR metrics above, but they can be valuable if creating a time-based fund model.

More on metrics at Metrics for Venture Capital Funds

GP and LP Economics

Many funds will want to show the return metrics separately for GPs and LPs, using the waterfall detailed above to forecast the cash flows to each party. Most fund models at this stage do not detail out the specific returns to each LP, except in cases when limited partners have different investment terms (potentially different carry, management fees, or ownership of a portion of the GP’s carry), which will require more detailed modeling to show the different returns to types of LPs.

Most funds will not detail out the returns to each GP in their fund model, but often managers will want to create a separate sheet or model to show the potential returns to each GP based on their individual general partner commitment and share of the carry.

Management Company Budgeting

So far, we have focused on modeling for the fund, but an additional concern can be in budgeting for the management company operating the fund. This can be valuable to detail the hiring plans and operational strategy for the management operational strategy, and important to show that the cash flows from the management fees can support the management company’s overhead. Modeling this is very similar to budgeting for any operating company, involving a forecast of hires and salaries, insurance, accounting, legal, and overhead costs, and using the fund’s forecast of management fees as the revenues for the management company.

Funds commonly misinterpret what expenses are paid for by the fund and what are paid by the management company. VC Lab has a good explainer at Managing Fund Expenses for Venture Capitalists.

Typically funds will model the management company through the entire fund life, but as the management fees from the fund expire, either (a) assume that they will raise another fund managed by the same management company, showing management fees from the new fund, or (b) show how the management company expenses will decrease over time. Typically this is not an important issue, as most fund managers will strive to raise another fund beyond the immediate one being forecasted, so any shortfall in revenues would be covered by the future fund.

Budgeting the Management Company of a Venture Capital Fund covers modeling a management company in detail. For additional detail on budgeting for Rolling funds, I wrote a post on budgeting for Rolling funds with AngelList.

Special Considerations in Venture Fund Modeling

Some special cases can create specific needs in creating fund models, I’ll cover each in brief but happy to answer additional questions by contacting me.

Revenue-Share Funds

The prior discussion of modeling proceeds assumes that the primary method for earning returns are through exits from the companies. Revenue-sharing funds typically make investments into companies that earn them distributions over time, in advance of exits, as a share in their companies’ revenues. The basic structure for modeling the fund still holds, except you will need to create a schedule of proceeds that aligns with the different timing expectations of revenue-share agreements.

The current suite of Foresight models work for forecasting the investments and all portfolio metrics for funds using revenue-sharing, but are not prebuilt to handle the calculation of proceeds from revenue-sharing over time. Fund managers can create a custom forecast of proceeds from revenue-sharing that can be linked into the core structure with minimal effort. For questions, contact Taylor.

Venture Debt Funds

Similar to revenue-share funds, venture debt funds invest using different investment structures, and tend to have different size and distribution of returns for their investments. The basic structure of the fund model still holds, except you will need to create a debt amortization schedule to show the repayments of principal and interest, as well as the proceeds from any equity share or warrants, will be necessary to model a venture debt fund.

The current suite of Foresight models work for forecasting the investments and all portfolio metrics for funds using venture debt, but are not prebuilt to handle the calculation of repayment of capital over time. Fund managers can create a custom forecast that can be linked into the core structure with minimal effort. For questions, contact Taylor.

Fund of Funds

Fund of funds invest in venture capital funds. While similar to modeling venture funds, typically you will want to create a schedule of new fund commitments to create a forecast of expected capital calls (structurally similar to a forecast of new and follow-on capital, except there are many more “rounds” of capital calls than follow-ons into companies). Typically we model the expected underlying value of the funds to report total fund-of-fund economics in a similar method to fund modeling.

Check out the free Fund of Venture Funds Model.

Crypto Funds

Crypto funds, whether they are structured as traditional funds or DAOs, are typically modeled in much of the same way as other funds. Typically crypto funds will hold more investments that can be marked to market easier, since many tokens will be traded on crypto exchanges, and funds will have more liquidity options, and thus will need robust structures to track token prices, liquidity timings, and track residual and realized value, but the same structure and metrics still apply.

The core Foresight models support crypto investments, often managers will want to customize the proceeds forecasts to capture the often earlier liquidity of these investments, and the typical phased selling of portions of their tokens. Once investing, fund managers will often want to use data tools to automatically pull in crypto asset prices for portfolio tracking purposes. Contact Taylor for any questions.

European v American Waterfall

In a total fund (or “European”) waterfall approach, the fund is required to return all of the called capital to-date before being able to share in the distributions through carried interest payments. In a deal-by-deal (or “American”) waterfall approach, the fund is required to return the cost basis of an investment (invested capital plus imputed fund fees) before sharing in the distribution on that investment.

A deal-by-deal waterfall allows fund managers to participate in distributions earlier than a total fund approach, but “clawbacks” are structured so that if later investments fail to return capital, then the carried interest paid earlier to GPs will be returned or "clawed back" to the fund. While the carried interest on each deal is different for an American waterfall, and the timing of carried interest is different, the total carry is the same for a European and American waterfall.

European and American waterfalls are detailed at Fund Waterfalls

For managers investing through a series of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) and modeling the aggregate of those vehicles, the waterfall works a bit differently. The American waterfall is commonly referred to as deal-by-deal, but to be clear, that does not mean that each deal is separate; the fund still has to return on the total called capital for all investments, and mangers can be subject to clawbacks if the aggregate carry paid out in the earlier periods does not pay the full cost basis of later investments that do not return capital. SPVs work differently, and they are true deal-by-deal, meaning one investment does not have to pay back the cost basis of other investments. Each SPV will often have different LPs, and the terms for each deal can be different, so this is a natural occurance. Important to note that all things being equal in terms of investments and returns, the same investments made as individual SPVs instead of out of a single fund (European or American waterfall) will result in higher carry being paid to the GP.

The current suite of Foresight models offer a dropdown select of European Waterfall (total fund to date), American Waterfall (deal by deal, with clawback), or SPVs Waterfall (no clawback). Additional details at Creating and Managing Investment SPVs.

Carried Interest

Carried interest, or carry, the "20" of the common "2 and 20" fee model, compensates general partners for the performance of the capital invested by the fund. Carry is calculated as a percentage of the proceeds to the fund above the return of paid in capital (for a total fund waterfall) or a percentage of the proceeds from an investment above the invested capital in that investment plus the cost basis on that invested capital (imputed management fees, operational expenses, organizational fees). For example, under a total fund waterfall if a fund had $100 million in paid-in-capital and $150 million in proceeds and a 20% carry, the fund would return $100 million to investors and then charge carried interest on the $50 million gain on investments (150 - 100), or 20% * 50mm = $10 mm in carried interest. Total distributions to limited partners would be 100 + 50 - 10 = $140mm.

There are additional considerations, of course. A fund could charge different carried interest to different limited partners, as detailed in the section on management fees. A fund could charge tiered carry, where one carried interest rate is charged on proceeds after return of capital and up to an agreed net return multiple or rate of return, and then a higher carried interest rate for proceeds above that net multiple or rate of return. If there is a tiered carry, there could also potentially be a "catchup" to allow the GP to earn what they would have earned at the higher carried interest rate on the proceeds they were paid at the lower carried interest rate.

Rolling Funds

AngelList’s Rolling Funds add a special consideration in modeling, since typically the fees are collected differently than traditional funds, and the waterfall is done on a per-period basis since each period (quarter) is a separate fund. For more detail, read How to make a budget for a rolling fund, which I authored with AngelList.

Foresight offers the model built for AngelList for free at Rolling Fund Budgeting template.

General Partner Commit

Some funds will model their waterfall treating the general partner commitment - the investment by the general partners into the fund, commonly called the GP commit - as a limited partner interest, some will not. If the fund treats the GP commit as an LP interest, then it is fairly straightforward to show the economics to GPs and LPs, as the GPs will take distributions using the percentage of the fund size that they invested in (GP commit divided by committed capital) plus their carried interest. If the GP commit is not treated as an LP interest, then the waterfall is amended to show the return of LP capital first, then the split between LPs and GPs using the carried interest percentage, and the GP’s returns do not include a portion attributed to their commit. This is a small assumption that most funds will not need to consider, if necessary it is a checkbox option in most of my models.

Note that management fees are typically not charged on funds invested into the fund via the general partner commitment, so the total management fees charged to the fund commonly will be less than you would expect if you just assumed fees to be a percentage of the total fund size.

All Foresight models are prebuilt to handle treating the GP commit as an LP or interest or not, simply check the box as appropriate and all formulas change automatically.

Recycling

Recycling allows investors to invest more capital. If your LPA allows you to recycle early proceeds from investments back into new investments (instead of distributing these proceeds to the investors in the fund) and to pay for fees, then many managers of funds will choose to recycle these proceeds, typically up to a percentage of committed capital or a percentage of the amount of the management fees charged to the fund, in order to boost their fund returns. There is extensive literature on the web about the incentives and reasons to recycle management fees; for capital budgeting purposes, we usually assume a percentage of management fees to be recycled (0 to 100%, or over 100% if managers are more aggressive) and add that back to increase invested capital.

Recycling is commonly misunderstood by emerging managers and can be difficult for managers to execute. Even if it is expressed as "management fee recycling", recycling fees does not decrease the total fees managers get, as recycling comes out of proceeds, not management fees. Many managers overbudget for how much they will be able to recycle, as LPAs often define (a) when recycling can occur, limiting it to a certain period, often the investment period defined in the LPA, (b) what it can be recycled into (new investments, follow investments, etc.), and (c) how much can be recycled (total proceeds from an exit, only the original invested capital into the company that exited, etc.).

All Foresight models are prebuilt to handle recycling with a couple options on how to use it. More details on recyling are covered at Recycling

Management fees based on invested capital

Modeling management fees based on committed or called capital is straightforward, but modeling fees based on invested capital (also called assets under management) takes special structural considerations. Since the fees are typically a percentage of the total invested capital at the end of each period, calculating the fees in spreadsheets creates a natural circular reference that is not easy to manage, and can be complicated for spreadsheets to calculate without more detailed linear optimization approaches. In practice most managers use an iterative approach by varying their assumptions to get total called capital as close to total committed capital as possible, but it can take some attention to manage model updates when using management fees based on invested capital

All Foresight models are prebuilt to handle modeling fees based on committed, called capital, and assets under management, simply select the appropriate option.

Evergreen or Open-ended Funds

Evergreen funds typically recycle a large share of proceeds back into new investments, maintaining a base of capital that is constantly recycled over time. Open-ended funds typically allow investors to redeem invested capital based on agreed timelines, and pay distributions over time. Modeling redemptions and new investors coming creates a couple of issues, and often requires calculating a NAV (net asset value) to use so that new investors are investing at a higher cost basis than earlier investors. With the recent announcement of Sequoia’s change in fund structure, this has created new levels of interest in open-ended funds or permanent capital structures, although it is still not a common structure for emerging managers to use.

LP side letters and varying terms

Some funds will create arrangements where different limited partners get different terms, namely either different fees (management fees or carried interest) or priority placement in the waterfall. Some funds will work with LPs to be first-loss capital, or may get a preferred return prior to other LPs, or they may get a portion of the GP carry. Each special term usually requires specific modeling for each consideration by breaking out the LPs separately, so the effect of each term can be clear.

Modeling multiple funds and SPVs

Often managers will invest through multiple funds, managing their primary fund, an opportunity fund, or special-purpose investment vehicles (SPVs) to make special investments outside of the fund with their limited partners. The best approach is usually to model each of these separately, and then combine into one comprehensive model, to show the cash flows and impact of each strategy separately and as a whole.

All Foresight models can support modeling multiple funds and separate investment vehicles. Users can duplicate the two core sheets creating the fund forecast, then link them into the Forecast sheet to create an aggregated view of the total investment strategy.

Management Fees, Cashless Contributions, and Fee Waivers

Budgeting for managers to pay their GP commit can be an issue for many managers. Managers may fund their commit from their own personal wealth, or pay for their GP commit using their management fees (post-tax), therefore reducing the net profits from the management company.

Management fee waivers are cashless contributions to the fund, where the fund manager chooses to satisfy some of their GP commit by waiving their management fees. The major rationale behind cashless contributions is to satisfy the GP commit without paying ordinary income taxes on the management fees waived to satisfy the commit, but that has significant tax implications and managers should consult experienced tax professionals before using this strategy.

Using your Venture Model

Creating a forecast is easy, making sure it’s believable is hard. Data on fund performance is sparse and difficult to collect, and typically best known by experienced fund managers and limited partners that work across multiple funds. Data can be specific to a certain time period or vintage, and may not be relevant for your strategy, geographical focus, stage, or current market conditions. Even data from known industry data sources CB Insights and Pitchbook can be more directional than statistically significant.

Three data sources that are regularly updated and available:

- Carta Data Desk is regularly updated with new research and analysis on the venture industry.

- Pitchbook – NVCA Venture Monitor. Updated quarterly with data and insights.

- CB Insights State of Venture. Updated quarterly with data and insights.

Scenario Modeling

Creating scenarios is an important way to think about your returns. There are two primary ways to define scenarios:

- Range-based scenarios, to evaluate different inputs and impact on outputs

- Situation-based scenarios, to evaluate different strategies

Range-based scenarios are typically done to show best, base, and worst case scenarios by varying the fund’s overall return multiples. They can be good for analyzing scenarios and discussing options with potential limited partners. Situation-based scenarios are typically better when you are considering how to structure the fund and evaluating different strategies, to show how the numbers reflect different fund strategies.

All Foresight models allow managers to use tools for scenario modeling, including Monte Carlo simulation tools and other Excel and Google Sheets add-in simulation tools. You can also create scenario tables in additional sheets to create your own scenarios based on the inputs you want to evaluate. More at Scenarios.

Tracking Actual Investments

Once you are actually making investments, it can be valuable to create a way to track your investments, create a specific schedule of capital reserves, and track your capital deployment pacing. Are you deploying capital faster or slower than expected? Are follow-ons coming in sooner than expected? Does your original budgeting strategy still hold?

Usually I will create one model for tracking investments, useful to help report investment performance to limited partners and internal team members, and one model for forecast, and then create a model that combines the two to aid in budget variance analysis.

The free model for venture portfolio tracking can provide a good structure to use for tracking investments in an angel or venture portfolio. The more advanced Foresight model combines tracking, forecasting, and variance analysis into a single model.

Strategy drives model, model reflects strategy

Don’t lose sight of the big picture. A model is an analysis tool, and is only as good as the data used to create the assumptions. Be careful using the model for portfolio strategy optimization decisions, as the data for benchmarking venture funds can be difficult to find and use for your specific model.

There are a number of additional resources that you can leverage to learn more. Join Slack groups for experienced or emerging managers, or groups like On Deck Venture Capital or On Deck Angels, of which I am an alum, or join accelerators like VC Lab, First Round Capital’s Angel Track, or Oper8r to get additional assistance in learning how to be an angel or venture capital investor. Learning how venture fund economics work is a valuable educational exercise for prospective angels and general partners, and an important part of demonstrating to potential investors the tactical operational knowledge of how investments generate proceeds and returns. Many emerging managers have learned the basics behind fund modeling on the job, realizing their gaps in knowledge once they had deployed significant capital, but today there are many resources and networks available to people that want to learn venture fund economics. Questions, ask anytime.